Catching Up With . . . Marion Sleet

“In the Nation’s Service” by means of “In Chicago South Side’s Service”

by Brooke C. Stoddard '69

Marion was born in St. Louis to a family of St. Louis people going back a long way. He lived in a segregated neighborhood. His father, a veteran, worked for the federal government. “The Mill Creek neighborhood was all Black,” Marion says. “It was poor by most “objective standards” but it had a vibrant social structure. Because of segregation, all social classes lived there, from the poor on up. The values were very traditional; there was a strong sense of community, and crime was low. All my friends were Black; I really didn’t see any whites. Having been a ‘border state,’ Missouri was not the Deep South, but segregation was pervasive, most notably in housing, education and accommodations.” Marion attended an all-Black elementary school.

Marion was born in St. Louis to a family of St. Louis people going back a long way. He lived in a segregated neighborhood. His father, a veteran, worked for the federal government. “The Mill Creek neighborhood was all Black,” Marion says. “It was poor by most “objective standards” but it had a vibrant social structure. Because of segregation, all social classes lived there, from the poor on up. The values were very traditional; there was a strong sense of community, and crime was low. All my friends were Black; I really didn’t see any whites. Having been a ‘border state,’ Missouri was not the Deep South, but segregation was pervasive, most notably in housing, education and accommodations.” Marion attended an all-Black elementary school.

Then came Sputnik. The nation tested for talent, and in the sixth grade Marion was chosen for a gifted-and-talented program. Three other schoolmates qualified as well, but there was no such program created in the Mill Creek community. So Marion and the three others took public buses an hour each way across town to an all-white southside middle school, both to integrate it and to take advantage of the special program.

“The first year at the southside school was rough,” Marion says. “The neighborhood was prejudiced, and bullies gave us a hard time. We weren’t the only ones hassled. They threatened a Jewish kid so badly, his parents withdrew him. The next year the school system moved the entire program to a smaller and more welcoming school.”

This one worked better. Marion attended Cleveland High School with many of the students from the program, sticking with this cohort of students up through high school graduation. Having had a choice of two high schools, Marion chose Cleveland High School, further south and near the Mississippi River, where he ran track and sang in the Glee Club. By this time there were about 10 Black students at the high school, though they were of two groups, one being the four students including Marion in the gifted program and the remainder from the Cleveland High School neighborhood;. His closest high school friends were the three other Black students from the gifted program, as well as his oldest childhood friends from the Mill Creek neighborhood and from church. Academically, Marion did well and received a Ford Foundation National Achievement Scholarship in his senior year. He recalls, “I had no particular preference for study in high school, though I was stronger in history, French and English than in math and science.”

Marion was looking to colleges in or near St. Louis, Washington University among them. “But during College Day at the high school I happened to sit at a table with a Princeton alum,” Marion says. “I knew nothing about the school except that the preacher pastor of my mother’s Presbyterian church had gone there and then into the Theological Seminary. Truth be told, at that time in my high school applying to the Ivy League was discouraged -- a guy ahead of me had flunked out of Cornell. Plus, the Ivies were thought, by some, to be snobbish with respect to Midwesterners. But my mother’s pastor was not like that; he was in fact an active integrationist.”

So Marion applied. Traveling around the country and looking for talent, Alden Dunham, Princeton’s Director of Admissions, stopped in St. Louis and interviewed Marion. A Merit Scholar, as well as the recipient of other scholarships, Marion received his Dunham-signed acceptance letter in April, 1965.

“I had only been out of Missouri once in my life,” Marion recalls, “and that was to Texas when I was five years old. I was not quite sure where New Jersey was. I researched Princeton in the library and learned it was regarded by many as ‘the southernmost of the northern schools.’” In the autumn of 1965, toting a trunk, Marion boarded a train for the East. Two more trains and 25 hours later, he pulled his trunk onto campus, and then to Brown Hall. Jeff Marston, David Lampen and Dave Butler were his roommates.

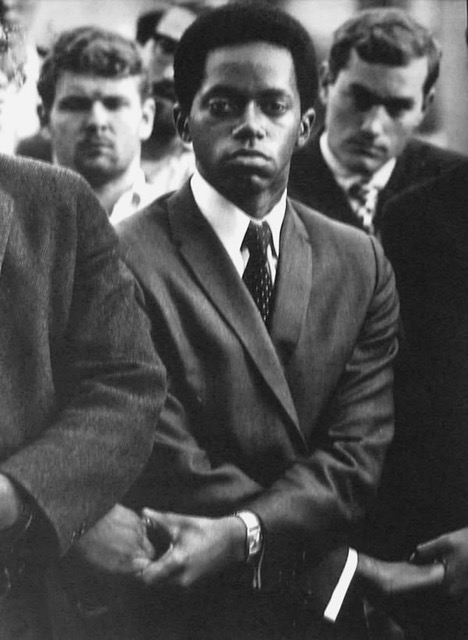

Marion majored in Sociology and wrote his thesis on Black students at Princeton, their attitudes toward Princeton and the dilemmas they faced. Marion was active in the  Association of Black Collegians. One of ABC’s actions was organizing the Chapel Service and campus-wide teach-in following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968. A photograph of Marion at that teach-in has become iconic for the Class of 1969.

Association of Black Collegians. One of ABC’s actions was organizing the Chapel Service and campus-wide teach-in following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in April 1968. A photograph of Marion at that teach-in has become iconic for the Class of 1969.

Marion also spent time with the Glee Club and received private voice lessons. He was chosen as a member of the Smith-Princeton Chamber Chorus that toured Europe in the summer of 1968. He is remembered for singing at a recent Class of 1969 Memorial Services at Reunions.

After graduating from Princeton, Marion moved to Chicago to enroll in the University of Chicago PhD program in Sociology. In 1975, he took a job at the Illinois Department of Mental Health, launching a career in the field of community and behavioral health that lasted until his retirement in 2015.

“At the time that I took my job with the State of Illinois, there was little understanding of the field of community mental health, particularly in Illinois. Historically, treatment took place in large public hospitals where mentally ill people were often institutionalized and warehoused. The advent of psychotropic drugs in the 1960s allowed these patients to be discharged from the hospitals. Unfortunately, the lack of community mental health facilities meant that these same patients repeatedly returned back into the hospital within thirty days or less. The major focus of my work was the development and growth of programs that ensure that people with mental and behavioral problems remain healthy enough to avoid hospitalization.”

His commitment to the growth of community behavioral health programs led to Marion working in and with multiple agencies and organizations on the South Side of Chicago and beyond.

At the Human Resources Development Institute he remained for 20 years, rising to senior vice president. Marion was instrumental in bringing the HRDI from a budding grant-nonprofit to a $25-million fee-for-service nonprofit in service of mental health, substance abuse treatment, criminal justice, and more to the South Side and beyond. In 2006 Marion joined the Ada S. McKinley Community Service LLC, a $40-million comprehensive social service nonprofit serving Illinois and beyond. He retired as its chief operating officer.

Broadly speaking, Marion has devoted his working life to improving south Chicago’s behavioral health; Ada S. McKinley works with the mentally ill, the developmentally disabled, substance abusers, foster care, youth programs, day care and more. Throughout his professional career, Marion served on the board of and briefly as a consultant to, the Illinois Association of Community Behavioral Health Agencies, the primary trade association of 90 community-based agencies across the State of Illinois.

substance abusers, foster care, youth programs, day care and more. Throughout his professional career, Marion served on the board of and briefly as a consultant to, the Illinois Association of Community Behavioral Health Agencies, the primary trade association of 90 community-based agencies across the State of Illinois.

There have been serious challenges to confront, but Marion has not succumbed to discouragement. “I’m an optimist,” he says. “Yes, severe problems persist, but I have been amazed by the successes that have been achieved through partnerships and collaboration among people and organizations. There are strategies that really work when you implement them properly. When we graduated, the phrase “Princeton in the nation’s service” was often thought of as people volunteering, as an aside, not as a career, but I think this is changing. ‘Service’ really is necessary for the well-being of our society. I really do believe that you can judge the quality of a society on how it treats the least of its people.

“In my view,” Marion continues, “a healthy society tries to help its members achieve healthy, productive and meaningful lives.. When it doesn’t, problems begin to spin out of control. Poverty should not be a death sentence. Mental illness is not a death sentence. You can live successfully with these if the right support systems are in place. Getting them into place has been a large part of my work, determining what is really effective and then delivering those systems to the people when and where they need them.”

In 2014, Marion received the Princeton Club of Chicago Distinguished Service Award for his career of service. “I was surprised to have been nominated and honored to be its recipient,” he says.

Asked about intellectual influences, Marion cites sociologist William Julius Wilson, whom Marion knew at the University of Chicago before Wilson moved to Harvard and who was author of Power, Racism and Privilege.

“I’ve had a fulfilling life,” he says. “I am most proud of my family. Camille and I have been married 51 years, and we have lived on the South Side in Chatham for 45 years. We raised two sons through public schools and who went on to have successful careers, one as a surgeon and the other as an attorney. So I’ve been blessed. Success comes in different forms coming out of Princeton.”

“I’ve had a fulfilling life,” he says. “I am most proud of my family. Camille and I have been married 51 years, and we have lived on the South Side in Chatham for 45 years. We raised two sons through public schools and who went on to have successful careers, one as a surgeon and the other as an attorney. So I’ve been blessed. Success comes in different forms coming out of Princeton.”